Corporate failure is a valuable asset that’s hard to protect

It’s important for organisations to understand the economies of negative information assets.

Investing in health and safety is potentially an untapped opportunity for businesses to recognise value on the bottom line.

My research, undertaken for a thesis through the University of Otago School of Finance and Accounting, explores whether the capacity of firms to manage health and safety could be valued as an asset rather than just seen as a compliance expense.

Health and safety has been a boardroom agenda item for many years and is a clear focus area for directors under the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015.

Feedback from directors, however, suggests that its importance has potentially receded relative to other issues such as the environment, cyber and quality.

One factor behind this could be that the financial consequences of poor health and safety performance in New Zealand are relatively low (compared to poor quality and or environmental performance) and the advantages of investing in health and safety are unclear.

While there may be changes to the future New Zealand legislative environment that bring the penalties for poor health and safety performance more in line with international comparisons, the ability to value health and safety capacity as an asset may provide a stronger driver for businesses to invest in that capacity.

The positive financial impacts of health and safety management have been subject to multiple studies. Research agrees that the financial benefits of health and safety capacity are reflected by increased productivity, lower turnover, talent retention, systematised innovation and, ultimately, improved share price when seen by corporate investors with a strong ESG focus, such as Australian superannuation funds and global infrastructure investors.

If health and safety capacity could be seen as an asset and potentially valued as such it may help to clarify the benefits of positive performance and better reflect the true costs of poor performance to the business.

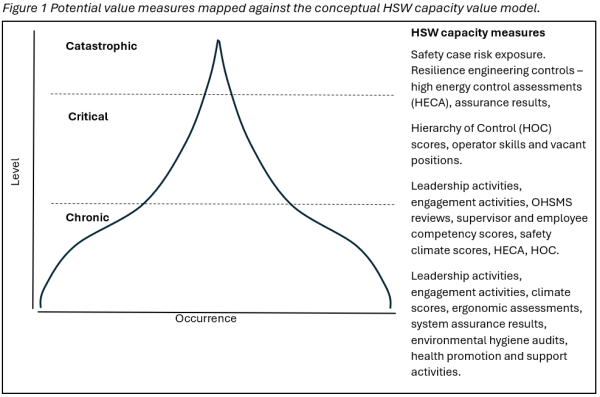

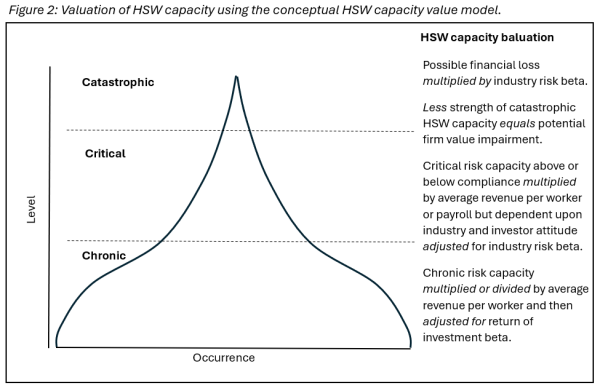

One potential valuation methodology requires health and safety to be treated at three levels – catastrophic, critical and chronic. These three levels have different valuation profiles.

The first level, catastrophic risk, is associated with large-scale industrial accidents and occurs rarely, if ever in a business’s lifecycle. However, if it does occur the consequences are not only catastrophic for workers and members of the public but also for the business itself in terms of reputational, financial and human cost.

The second level, critical risk, is associated with serious injuries and fatalities (SIFs) from acute harm incidents that usually attract legal penalties – in some cases reputational damage and a moderate-to-low level of business disruption. These again happen rarely for individual businesses but can take up considerable management and governance focus.

Thirdly, chronic risk is the most prevalent level within a workforce and includes both physical illness and risks to mental wellbeing. It is highly likely in any workforce that chronic illnesses such as musculoskeletal diseases, depression and anxiety will be present at any given time.

There are different strategies for effectively controlling risk at each level, differing drivers of success and different value creation opportunities. For the catastrophic level, there may be little or no additional advantage beyond having the capacity to avoid large-scale industrial accidents. However, there are serious financial penalties for organisations that are not perceived as having the minimum required level to avoid catastrophe.

As most catastrophic risks are also highly regulated, not meeting minimum standards should become a due diligence issue for acquisitions, or be reflected in share price.

The capacity to manage critical risk has greater potential upside financial advantage because it is associated with wider professionalism, better management systems, retention of staff and intellectual property, as well as stimulating ideas and innovation which all lead to productivity and efficiency gains.

There may be some financial disadvantage to not having capacity in this area but this is not generally associated with strong regulatory penalties.

The greatest upside financial gains are potentially in the chronic level where there is clear evidence that a workforce that suffers less from chronic health issues is more productive, effective and stable – giving businesses long-term competitive advantage and resilience.

Understanding how to value health, safety and wellbeing capacity requires a common method for the interpretation of fair value and an estimation of future cash flows to meet the accounting definition of an intangible asset.

Given the three different levels of health and safety risk, a conceptual model may assist in developing valuation methodologies at all levels. If capacity can be measured at each of the three levels (figure 1) then a potential valuation calculation based on those measures could be derived (figure 2).

The model is conceptual currently but designed to fulfill a need for investors and valuers who desire to understand the financial impacts on firm value for their investment in health safety and wellbeing capacity.

Further quantitative testing is now required to develop the model and to determine whether it meets the needs of external and internal businesses stakeholders.

Ultimately, directors should be able to understand the value inherent in the company’s investment in health, safety and wellbeing capacity.

Accounting for that capacity in a standardised way should lead to better direction of resources and decision-making – to better protect the worker and benefit the business.