Advisory boards: what they are and how they operate

Advisory boards sit alongside governing boards and the management to provide insights that benefit both groups.

The rise of advisory boards is a boon for growing companies. It also carries risks.

The IoD published a good piece by Kendall Langston about advisory boards last year. Their purpose is to provide strategic (and fearless) advice from trusted advisers familiar with the business, and a robust platform for working on the business rather than in it. They cannot make decisions nor govern.

In a sense they are a group of consultants on retainer. For start-ups they may be a ‘try before you buy’ option before establishing a formal board.

Another model is that advisory boards can supplement formal boards, bringing specific expertise, sometimes for a fixed period.

We should pay attention to advisory boards because as this report reveals, an analysis of LinkedIn profiles shows a 52% increase in the number of advisory boards across the globe since 2019.

It also describes ‘a distinct shift in how professionals are seeking to engage at a board-level – with an increasing move away from traditional governance board/director roles into advisory board roles’, although it doesn’t say why.

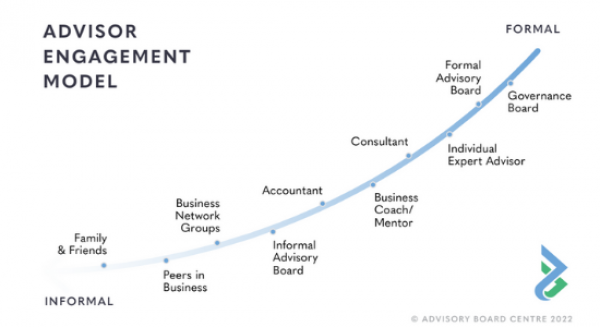

The report takes the ‘try before you buy’ model further by positing that advisory boards reflect just one stage of maturity as this diagram shows:

Advisory Board Centre 2022

Advisory Board Centre 2022

Talal Rafi, a member of the Forbes Business Council, is a fan. He claims that 86% of businesses with an advisory board say ‘it has a significant impact on its business’. The study he cites shows sales up 24% and a productivity increase of 18%. He also sees them as being just as much an option for large companies, citing Toyota which established an international advisory board which includes ex-prime ministers and the like. The latter is an example of where credibility and networks are added to the benefits of additional advice.

Rafi also points out that they are cost-effective and flexible because they are easy to establish and disestablish, and fees tend to be lower.

The two risks I see, certainly in New Zealand, may both be unintended consequences of the increased responsibilities of company directors.

The first I wonder about is experienced businesspeople simply avoiding director liability. A shareholder/investor on an advisory board can probably access as much information as they need to understand the company and the context, opportunities, risks and so on. Unless there is ill will, they may have all the influence they are looking for too, so they get the voice but not the liability. Many – especially in private companies – will have little interest in the perceived status of being a full director, and the distinction is probably lost to casual observers anyway.

This may not matter unless the consequence is that formal governance is concentrated in the hands of two or three founders or long-serving executives/shareholders and the firm is scaling up.

The second unintended behaviour is firms avoiding the compliance burden and general overheads of a formal board. It’s easy to sympathise when you hear CEOs reflecting on the amount of resource devoted to preparing for board meetings and the aftermath, especially if they are monthly. Advisory boards do not govern though, so that creates a risk of dominance by management, or worse, an illusion of independent governance.

The 2021 report refers to this risk, and perversely illustrates the danger of confusion when it states (emphasis mine) ‘With the increased utilisation of advisory boards in a governance framework, boundaries are tested and a lack of good governance will be exposed. Adopting best practice will assist in providing transparency of purpose and role clarity internally and to the market for public’.

I agree with the analysis and the response, but not with the use of phrases like ‘in a governance framework’ which just blurs the line again.

Advisory boards are an excellent tool to improve performance, but we need to be clear about when they are the first best option, and not avoid a conversation about governance.

Kevin is a founder of MartinJenkins and has over 30 years’ experience as an advisor to business, not-for-profits and government. He works with boards and executives to help them clarify their strategic direction and make the best choices to achieve their purpose and goals.

He currently chairs the advisory board at the School of Government at Victoria University of Wellington, and is a member of several other advisory boards.

The views expressed in this article do not reflect the position of the IoD unless explicitly stated.

Contribute your perspectives and expertise on an area of governance to the IoD membership and governance community. Contact mail@iod.org.nz